Imagining ≠ Understanding

Jul 15,2016

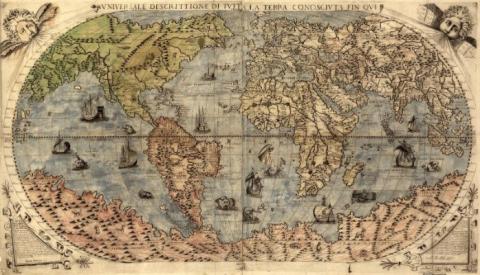

Your eyes have just now jumped from the image of the map, to the title of this article, and now to each word of the first paragraph. You're trying to discern what this LinkedIn post is about.

If you're like most people, I've already lost you. You've jumped from the first paragraph to somewhere in the middle, attempting to understand the article by imagining what sentences might glue together the one's you've actually read. If you're not like most people, you have not yet skipped a single word or phrase. You're reading this right now, in its sequential entirety. If you have read every sentence so far, I must commend you.

The act of skimming—skipping and mentally filling in things not understood—leads to inaccurate perception. The people who created the map shown above were unintentional skimmers; they had only explored so much land before creating a map of it. Imagination is a fantastic thing, but it can lead to a skewed understanding of reality, when used as intellectual caulk for gaps in information.

Visual scientists tend to agree; the following is an excerpt from “Representational Correspondence as a Basic Principle of Diagram Design,” by Christopher F. Chabris and Stephen M. Kosslyn:

For well over 100 years researchers have reported that visual imagery interferes with visual perception—as expected if the same system is used in both cases. For instance, researchers showed that visualizing impairs the ability to see (Perky, 1910; Segal & Fusella, 1970). Later researchers documented that people falsely remember having seen an object when they in fact only visualized it (e.g., Johnson & Raye, 1981). And yet other researchers focused on functional similarities between imagery and perception (for reviews, see Finke & Shepard, 1986; Kosslyn, 1980, 1994b). For example, objects in mental images require more time to imagine rotating greater amounts, as if the images were literally rotating about an axis (Shepard & Cooper, 1982). Similarly, people require more time to scan greater distances across imagined objects, as if the imagined objects are arrayed in space. Moreover, they require more time to “zoom in” greater amounts when “viewing” imagined objects (Kosslyn, 1980).

In other words, the act of imagining something actually impairs one’s ability to accurately understand it. When one visualizes something, that thing’s most memorable attributes are stored the most intensely (in essence, imagining requires visual hyperbole as a means toward memorability). The lesser attributes are stored not nearly as intensely, and so they are, in a way, reverse-exaggerated.

Skimming, then, is even more misleading than you might have thought. However, striving to do the opposite—over-viewing—is also dangerous. A design’s first impression—the first visual event which catalyzes the formation of a mental image of the design—is of paramount concern to designers, yet there is a time limit for realistic viewing, after which the act of viewing is misleading.

Designers can easily lose their first impressions on whatever it is that they are designing, and when a designer’s view of an item becomes dysmorphic, his or her subsequent design decisions can become detrimental to the design. The audience can also lose their first impressions of the design, but the audience's viewing priorities lack the overarching lens of design, through which the designer was able to build the used product.

Thus, this design lens is both a gift and a curse. Designers are trained to maintain a sharpened eye, but doing so requires active viewing: a process that can easily lead to over-viewing and dysmorphic viewing. The one thing that mediates this danger, the problem of designers and users having different views, is distraction between viewings. Designers will always have other things to design between critiques, and users will always have other things to view between return usage of the product.

In this way, the mental image of both designer and user is constantly replaced, so the first impression—to the benefaction of both viewing parties—is in a constant state of regeneration. All of the things viewed in between act as distractors, leading to the underscoring of the first impression.

In a way, it's the opposite of skimming. Whereas skimming is actively curating which content to view in order to quickly form an opinion on something, reverse-skimming is actively forcing unrelated content in between viewings in order to underscore that unbiased first impression.

So what does all of this mean? It means that there is a spectrum: on the left is skimming and on the right is over-viewing, and right in the middle is understanding. You can skim something, and only partially understand it; or you can over-view something, and misunderstand it; or you can view it a healthy number of times, and truly understand it. And if, by chance, you overview, simply forget about it for a while before revisiting for a refreshed original perspective.

Thus, if you've skimmed this article and are finishing up by reading this sentence, I commend you for using a cognitive technique for speedy absorption. However, if you want to understand why you just did so—not to mention, if you want to understand the point of this article—feel free to scroll back up and look again.