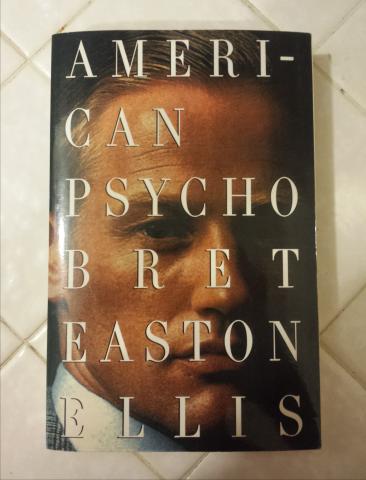

Book Review: Bret Easton Ellis' "American Psycho"

Apr 10,2016

Even people who have never read Bret Easton Ellis' American Psycho likely do not expect to hear the phrase "comedy of manners" in reference to it. Comedy of menace maybe, but definitely not comedy of manners. Yet Ellis' engrossing tour de force preoccupies itself as much with its protagonist's interactions with his peers as it does his with his sadistic behavior. As well-known as the book is for the latter, readers and critics almost miss the point of the novel by focusing on this psychotic brutality at the expense of the nonviolent transgressions he commits, which are less bloody but no less cruel. In fact, it is these subtle acts of cruelty, not the over the top descriptions of gore and sex, that stick the most with the reader.

A well-to-do Wall Street banker, Patrick Bateman is on top of the world in late 1980's America. He dines in the finest restaurants with his equally well-to-do friends, he has his pick of "hardbodies" (the term he and his friends use to refer to attractive women), and he has the finest clothes and the newest goods. He always knows the right thing to say and has all the correct opinions, telling his enraptured companions that the country needs to "provide food and shelter for the homeless and oppose racial discrimination and promote civil rights while also promoting equal rights for women but change the abortion laws to protect the right to life yet still somehow maintain women's freedom of choice." (Ellis, pg. 16) Yet Bateman is unimpressed by the life he leads. He absolutely detests his friends, including his best friend Timothy Price, whom he despises most of all. Any thrill he gets from chasing after hardbodies dissipates the moment he gets what he wants from them (that is, violent sex that regularly spills over into simple violence). He enjoys wearing the nifty suits and using the high-end goodies he has access to, but the effort he puts into mentally cataloging them to readers and himself seems to deprive him of any real pleasure he could derive from them.

The thoughtful and charming persona he adopts, of course, is a total fraud. What others mistake for politeness is an almost-demonic ability to read others and determine what they want to hear. Beneath the mask of agreeableness is a man ready to explode at the slightest provocation, as he does when one of his friends has the misfortune to get on the last of his many nerves. Irritated that nobody is responding to his repeated requests for a pizza, Craig McDermott snaps and hits the table the group is sitting at. "...I suddenly raise a fist as if to strike out at Craig and scream, my voice booming, 'No one wants the f***ing red snapper pizza! A pizza should be yeasty and slightly bready and have a cheesy crust! The crusts here are too f***ing thin because the s***head chef who cooks here overbakes everything!" (Ellis, pg. 46) This is the real Bateman: not the calm, urbane yuppie, but the cruel, crude psychopath ready to lash out at anybody unfortunate enough to cross paths with him. And as for his purported concern for the downtrodden, consider these two things Bateman says to a disabled Vietnam veteran begging for change and a homeless African-American whose eyes, mind you, he just gouged out when nobody he considers important is around: "You never were in Vietnam," (Ellis, pg. 386) and "There's a quarter. Go buy some gum, you crazy f***ing n****r." (Ellis, pg. 132)

In short, Pat Bateman is a thoroughly wicked individual whose excesses say as much about the absurdity of many social conventions as it does his own depravity. Indeed, the most chilling thing about the book is the ease with which this obviously unstable man is able to blend into the highest echelons of society just by memorizing the behaviors and codes that are practiced within them, but it's a talent that serves Bateman well. In spite of several close encounters, including a car chase and shootout with police that may not have actually happened, he is never called to account for his many crimes and sins. Instead, we are left with the central realization Bateman reaches about himself: "...there is an idea of a Patrick Bateman, some kind of abstraction, but there is no real me, only an entity, something illusory, and though I can hide my cold gaze and you can shake my hand and feel flesh gripping yours and maybe you can even sense our lifestyles are probably comparable: I am simply not there." (Ellis, pg. 376-377) His epiphany is followed by him doing what he was doing at the beginning of the novel: going back and forth with his colleagues over dinner.

Needless to say, this is not a novel for the faint of heart. Even if you set aside the wanton scenes of killing and fornicating, there are obscenities, slurs, and all around unpleasantness that will make many wince. Not to mention, Bateman's almost encyclopedic reciting of minute details about his and other people's possessions may very well sap readers of their stamina or interest. If you can look past the minutiae, the profanity, and yes, the gore of Bret Easton Ellis' American Psycho, however, you will be treating yourself to one of the sharpest insights into modern society as well as the human condition in contemporary literature.

Schedule